App Store Heresies: Higher Price, Better Ratings. Don't Discount Your App At Launch.

Lower your price, lower your ratings. Lower ratings, lower social proof. Lower social proof, lower sales. That’s my theory, and I’ve got data to support it.

I’m a pattern matcher. I like extracting the hint of a signal from noise. For a while now, I’ve had a hunch that pricing an app higher would lead to better ratings. Been reading Predictably Irrational and Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion.

So when, in the closing days of summer, I saw Pete Schwamb tweet about the ratings decline he saw for Cricket Song (his clever app that tells the temperature by listening for cricket chirps) when he starting giving the app away I filed it away as a data point. A short time later, I read Andrew Binkowski’s blog post A Week At $0.99 and noted that the ratings for his baby naming app Stork Drop dove after cleaving 2/3rds off the price.

I sometimes bury the headline; so I’ll state it now, then back-fill the supporting data:

Don’t Discount Your App At Launch

Conventional iPhone buzz-building wisdom tells you to launch your app at a fraction of your real price. Don’t.

During the early days of an app’s life, social proof is critical. Social proof is how you decide whether or not to jaywalk in a new town: you look to see what others do. More formally, social proof is:

a psychological phenomenon that occurs in ambiguous social situations when people are unable to determine the appropriate mode of behavior. Making the assumption that surrounding people possess more knowledge about the situation, they will deem the behavior of others as appropriate or better informed.

Applied here, social proof means that ratings provide prospective buyers a peephole into the reasoning of the assumed-to-be better informed earlier buyers.

So, it’s important to maximize your rating early on. Discounting your app won’t maximize ratings:

Data

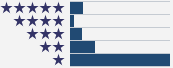

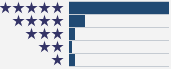

Start with the Christmas tree lights test: to ensure even light-coverage step back from the tree and squint at it. Squinting blurs the lights, causing them to fill in. It’s easy to see — and fix — gaps. Try the same thing with the ratings-distribution graph in the App Store; squinting blurs the specifics and presents the general shape of the curve. On the whole, you’ll see that the graph’s weight for free apps shape sags towards 1 star. As you move up in price the weight shift to the top of the chart where the better ratings live.

|

|

| Free App | $2.99 App |

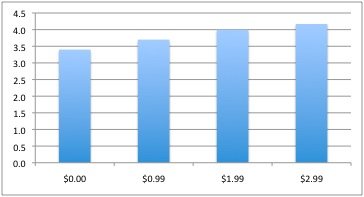

Compare the the top-10 paid and free apps. The average rating for top-10 paid apps is 3.9. Free apps average 3.4, half a star’s difference!

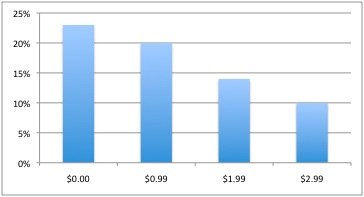

What’s more, when you break the apps down by price you’ll see that every price increase is accompanied with a ratings increase:

Wrapping Up

Pete’s tweet hit the nail on the head when he labeled the folks who got his app for free as uninvested users. Customers with some skin in the game cary a psychological pressure to feel that they’ve been wise in their purchases; they’ll tend to over emphasize their positive feelings.

What’s more, I’d bet that the likelihood of a user uninstalling an app goes down with its costs. Uninstalling apps triggers the negative review bias.

I’ve got two somewhat related items that I couldn’t fit in elsewhere:

1. The “Sex Jokes Lite” application is clever/manipulative about their ratings. They push people to give 5 star reviews with this little bit of a social contract: in their app-description they say, “IMPORTANT: If you think the jokes are TOO dirty, please give a 1-star review. If you want them dirtier, give a 5-star review. This way we know what direction to take in the upcoming updates !”

2. I’m interested in the number of ratings and number of reviews as compared to total of installs on a category by category basis. Games have a small ratio of reviews and ratings to total downloads. I’m curious about this more broadly. Have data? Leave a comment or email me.

Beginning iPhone Programming: Portland/OR Nov12-13, Los Angeles/CA Nov19-20

iPhone OpenGL Programming: Bay Area/CA Nov19-20

I think you have very good point in general but that you are missing the data to support it properly from the perspective of app pricing. Since the main thing we are concerned with when selling an app is making money, not necessarily getting the highest reviews (though of course that helps), the real question is whether higher prices lead to more overall $s. It would be great if you could add some data about the total number of downloads per app per price to help us see where the sweet spot lies. You also have a major confound to deal with when looking purely at the appstore data without paired samples – maybe the more expensive apps actually are better overall and hence deserve better ratings.

Good points. I have a feeling, though, that my targeted audience (college students, who tend to be cheap) may knock my fairly simple app in the reviews if I launched at anything more than $2.

I’m also concerned about impulse purchasing. When I see an app over $2 or $3 I hesitate to purchase it. I bet I’m not the only one, especially among college kids.

Regarding making money, we have noticed that ratings have a large effect on sales. When our ratings are higher, the sales reflect that. Cutting the price in half did not double sales, so was a net loss.

I’d be careful when drawing conclusions from the data you presented. An equally valid conclusion could be that free apps are of lesser quality than paid apps, and the higher the price, the more effort has been put in by developers, hence the apps are objectively better.

@jan: it may be true in general that free apps have lower quality, but when you limit the set to very, very popular apps I don’t think that’s the case.

What a great article. I have seen this data supported in my own experiences over time. I initially subscribed to the thought that a) I had to have a free “lite” version and b) I had to jumpstart sales at $.99. I couldn’t have been more wrong. As soon as I moved my price up to $1.99, I saw less poor reviews and more “invested” reviews, and my sales are still steady.

I’ve found free apps or $.99 apps get a lot of snap judgement reviews, it’s a 1 or a 5 strictly based on if they don’t use it a lot or if they do. Nothing towards the quality of the app.

I think the low number of reviews vs total installed is primarily due to laziness. I’ve spent money on many apps that I use regularly and are extremely happy with. While I’d rate them highly, I haven’t done so because I have to go back to iTunes to rate it or I have to uninstall it (perhaps there’s an easier way that I’m unaware of?). Your post has reminded me the importance of reviews, so I’ll go and review those apps that I use regularly and enjoy.

Until now, I think that all of my reviews have come when I’ve uninstalled the app and the helpful rating dialog pops up (and in those cases there’s definitely a bias since I’m purposefully getting rid of the app). I think it would be nice if after N uses that dialog popped up immediately after launching or quitting the app. At that point it’s as easy to review the app as it is to close the dialog.

I’m going to disagree here too. Correlation does not equal causation.

As Jan said, you are assuming the only variable is price and that actual app quality does not go up with price. There certainly may be some effect due to price alone, but you can’t draw too many conclusions from it.

arn

arn: I have never seen you post a positive comment here. why so negative? do you need a hug?

One subtle bias factor is that Apple asks you to rate an app on deletion. I’ve deleted plenty of free apps but I don’t think I’ve ever deleted a paid app because.. dammit, I paid for that thing. If you make your app free, you end up getting a lot of people trying it out, it being not for them and them rating it 1 star.

This might also explain why games aren’t rated as much since fewer people delete them compared to toy apps.

I believe I have only posted 2 comments here. 🙂 I don’t think they have been particularly negative. Just pointing out why I disagree with the points made.

arn

You’ve discovered something I learned as a child. My mother’s philosophy was: “If it costs a lot it *must* be good.” Which just didn’t make sense to me – [erhaps because my father’s philosophy was: “How much? I can make it for half that and be paying myself $X/hour with the difference.”

I had this reinforced many years later when I did a very brief stint selling hardware – in particular, large (for then) capacity disk drives. Now one well known company bought drives off another well known company and stuck their label on them, marked them up 400% and then re-sold them. Our company tried buying the same drives, leaving the OEM’s name on (since they were quite well known) and marking them up 10%. People would not buy them. They couldn’t believe something so cheap was just as good. Even when you had them look inside the chassis of the 400% mark-up units so they could see that not only were they made by the same company as ours but even had the same part number on them! And the OEM was backing the units with an equivalent warranty to the expensive drives. It was only when we started adding large mark-ups, but still less than 400%, that sales appeared.

I subsequently raised cricket song back to 99 cents, and the negative ratings basically stopped. I would guess that apps that appeal to a narrow market suffer more from this effect than apps designed to appeal to a wide market, like games. If someone who had no interest in nature trivia or crickets downloaded my CricketSong app just because they were bored and it was free, how likely would they be to give it a positive rating?

How is this affected with the new announcement of in-app purchases for free apps?

I absolutely agree that higher prices lead to better reviews.

However my experience so far is that reviews seem to have less influence on sales than you’d expect. As developers we tend to pay a lot of attention to reviews and some unjustified negative reviews really bother us. However users don’t seem to pay all that much attention to reviews and ratings. I am not saying they don’t matter at all, but they seem to effect potential customers way less than we developers tend to think.

@hkk: I believe that you’re right. I’m not an iPhone developer, I’m just a customer and I never bought a game or application after reading reviews, instead i read them to decide if I download an application or not. There’re so much apps in the store and even downloading them is an invesment in terms of time. I’ve never downloaded an app which has got bad reviews in total.

Purchasing is all about satisfaction for me. If I love the concept, I go and purchase, at this point I don’t care what other people think about!

If I discover any app socially, I mean a group of friends for example, I download it without reading any reviews or checking the ratings.

i’d like to see some data that uncovers ratings vs profit. if we have all five star ratings with a $49 app, great, but who cares if we’ve only sold a few copies of the app at that price.

Lar Van Der Jagt – lets see your data!

Ah! You are describing the Principles of Social Validation and Scarcity as which I write about in the book Neuro Web Design: What makes them click?

Dan,

I believe you are correct. I just finished reading the book, Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely. One chapter focused on the power of price. Basically the higher a price for a product, the more positive people feel about the product in order to justify their purchase. People will report greater effects from medications when they pay a higher price versus a lower priced alternative with the exact same chemical composition.

I have 3 simple apps and I was experimenting with price lately.

All that you guys are saying is correct in one way or another. You make one app free, there will be lots of downloads and reviews.

The reason: there are websites and blogs that are publishing any price decrease and it looks they have lots of followers.

The followers are downloading the app just because it is free, not because they have some use of it. The uninstalled it soon and they rate it depending if they liked it or not. As they are uninstalling it, it is obvious that they did not like it.

So, as said above, asking somebody to rate an app when they are uninstalling it does not make sense. It is like asking somebody to rate a product they are returning for a refund to the a store.

I’m unconvinced

Usually if a developer has placed a app on the store for a price they have spent long hours getting it right.

I wouldn’t be surprised if half the crap free applications were developers testing the app store. Thus these apps are never going to be any good and as a result get bad reviews.

I also agree with the previous posts on the rating system, you rarely go out and rate or review an app unless you uninstall it or is so super.

This leaves out the middle range apps without many reviews..

Jake 10.20.09 at 9:48 am

Dan

I believe you are correct. I just finished reading the book, Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely. One chapter focused on the power of price. Basically the higher a price for a product, the more positive people feel about the product in order to justify their purchase.

I guess steve Jobs worked that out years ago.

It’s clear that there is a correlation between app price and ratings. That’s interesting, but by itself not useful. You provide reasonable explanations for why some portion of the rating is tied to the price people paid and not application fitness. You also have some anecdotal evidence that support this, but it’s an incomplete picture.

What’s most useful is knowing all of the most significant causes of this correlation. An app’s rating is partly based on it’s fitness, and partly on confounding factors – artificially inflated paid reviews, rating sabotage, fortunate reviews, group-think, method of selecting of raters, etc. How much each contributes to the rating is probably very complex, and factoring out one dimension with only anecdotal support isn’t enough for me.

I don’t doubt there is a correlation between price and rating, but I am not convinced that the *major* reason for this is some kind of emotional economic response. I also don’t see any significant evidence that says a low starting price would reduce your initial rating.

It seems that developers are also subject to the effects of social validation in pricing their apps. Everyone else prices low, so you price low. I don’t see any other rationale used for pricing apps. Well, I guess raising the price to try to avoid low ratings could be one rationale, but you don’t know the correlation to sales.

Running pricing experiments is flawed. Price too low, and you may insert negative reviews that will influence future experiments. Pricing too high could lead to the same problem, as disappointed buyers complain the app isn’t worth what they paid.

Why not actually do some research into pricing your apps?

Check out the Van Westendorp method of value pricing at 5 Circles Research.

I’ve had some experiences that have also suggested that there is actual causation at work (as opposed to simply correlation). One interesting observation is to take a look at Tap Tap Revenge 2.6 (which was .99) versus Tap Tap Revenge 3.1, which is free and relies on in-game purchases of “hit” songs for monetization. Tap Tap Revenge 2.6 is a solid 4 stars, while Tap Tap Revenge 3.1 is barely 2.5 stars. They are different apps, but not *that* different.

It may be the case that it doesn’t really matter– Tap Tap Revenge may have enough of a following that Tapulous is currently pursuing a profit-maximizing path with 3.1 even though it is tanking their ratings. In any case, while it may not be completely valid to generalize from this one anecdote, it would appear to me that something stronger than correlation is happening here.

Regardless, I strongly believe that Apple should stop asking for a rating upon deleting an app. That is clearly a confounding factor and does a disservice to everyone. If an app is sufficiently good that you want to tell others to get it, great. If an app is sufficiently bad that you want to tell others to stay away, great. But don’t create artificial mechanisms to skew the numbers one way or the other.

I like how everyone who disagrees has even less (if any) data to back up their own assumptions.

Folks, if you disagree offer something to show why you think that, otherwise you’re just taking up space. The burden of proof is on you, after all. Dan’s done his job and offered actual, not anecdotal, evidence. It may be sparse but it’s more than anyone else has offered.